What is the higher education accreditation process, and what are Southern states considering changing?

DOWNLOAD

Unlike other Western countries, the United States has no single, centralized federal authority that exercises nationwide control over its higher educational institutions.

Enter accreditation agencies.

Instead, states and individual institutions often operate with varying degrees of autonomy, which leads to variations among states, institutional systems, and individual campuses.¹

Accreditation is a non-governmental, peer-reviewed process for evaluating educational institutions and programs.³ A peer review involves evaluating a body of work by a group of individuals in the same profession or field, which is typically utilized to maintain the quality of professional performance.⁴ As part of the U.S. Department of Education’s processes, the peer review process involves a group of panelists reading, evaluating, and scoring submissions using a rubric and scoring criteria published by the department. Despite the lack of centralized accreditation, the federal government still retains an outsized role in determining the legitimacy of accreditors.⁵

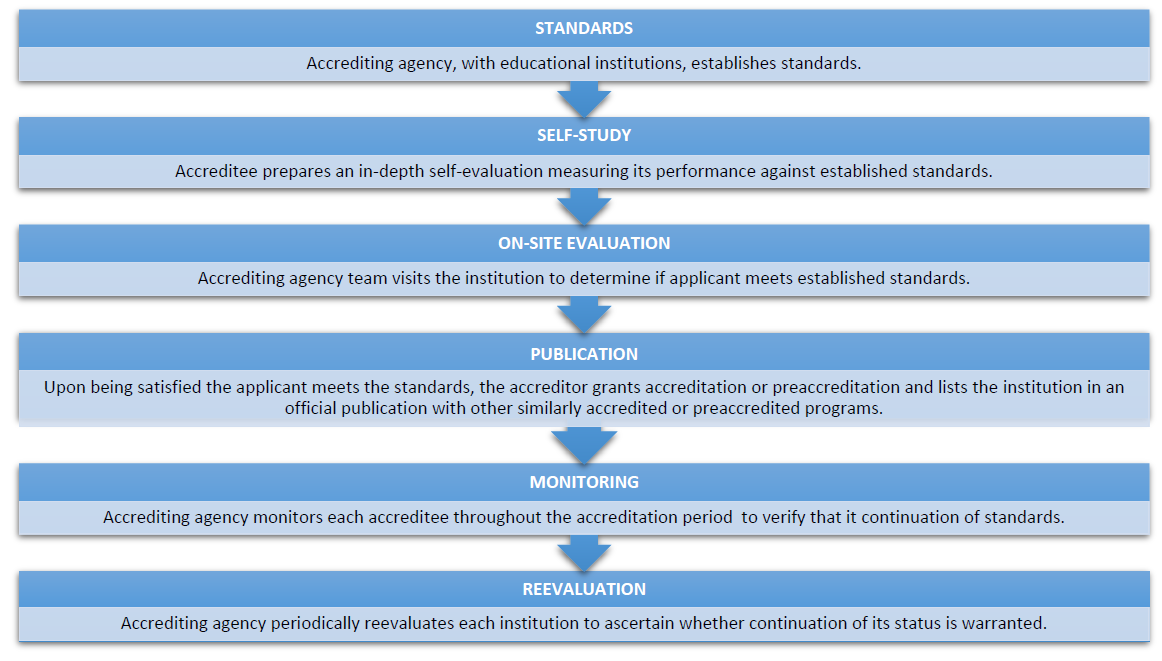

Section 114 of the Higher Education Amendment Act of 1992 and Section 106 of the Higher Education Opportunities Act of 2008 authorize the National Advisory Committee on Institutional Quality and Integrity (NACIQI) to advise and provide recommendations to the U.S. Secretary of Education as to the accreditors that it deems eligible and qualified to serve as recognized accreditors for colleges and universities in the U.S.⁶,⁷ Further, federal law requires institutions to be accredited by recognized national or regional entities to access federal student aid. Per the U.S. Department of Education, the accreditation process typically involves six steps:

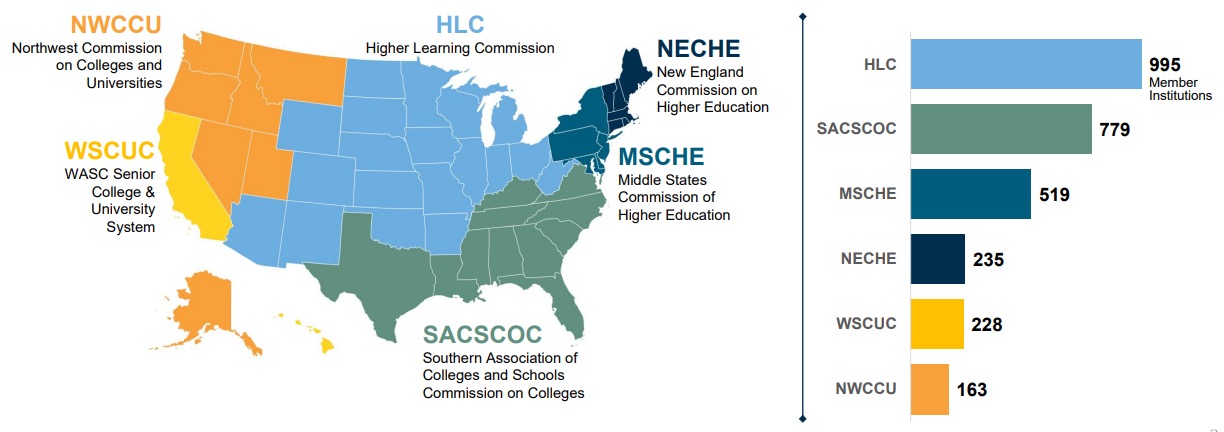

FIGURE 1. Comparison of Major Regional Accreditors

FIGURE 2. The Typical Accreditation Process

However, federal and state lawmakers have recently expressed skepticism over the processes surrounding existing regional accreditors, including the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC), particularly focusing on inputs, including faculty credentials and facilities, instead of institutional outputs, such as graduation rates, post-degree earnings, or student debt ratios.¹⁰ This chorus of current concerns joins the more longstanding, cross-partisan concerns surrounding the tedious accreditation process and the administrative burdens institutions face. Additionally, both the new and old generations of accreditation reformers have brought attention to the oversized boards and subgroups comprising the current slate of recognized accreditors as a barrier to responsiveness and innovative practices that require quick actions.¹¹

Into this ongoing debate, state policymakers, particularly in the South, have stepped up to reconsider the accreditation process and examine the opportunity to create new, more output-focused accreditors.¹² However, a review of the current landscape is necessary before jumping into the recent trends. Public institutions in the South are typically accredited by one of two accrediting agencies, the aforementioned SACSCOC or the Higher Learning Commission (HLC), both of which were founded in 1895. Prior to the founding of these and the other regional accreditors, the South lacked a unified system of higher education accreditation, which was still a voluntary process.¹³ It was not until the passage of the 1944 Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, more commonly known as the GI Bill, that the floodgates of federal financial assistance to institutions of higher education opened, prompting a rapid turn toward accreditation as a necessity.¹⁴

TABLE 1. Comparison of CSG South State Accreditors by Number of Public Institutions Accredited

| State | No. of Institutions (SACSCOC) | No. of Institutions (HLC) |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 51 | – |

| Arkansas | – | 48 |

| Florida | 74 | – |

| Georgia | 78 | – |

| Kentucky | 50 | – |

| Louisiana | 41 | – |

| Mississippi | 32 | – |

| Missouri | – | 76 |

| North Carolina | 111 | |

| Oklahoma | – | 43 |

| South Carolina | 51 | – |

| Tennessee | 61 | – |

| Texas | 152 | – |

| Virginia | 70 | – |

| West Virginia | – | 31 |

Federal and State Reforms

As part of the 2024 College Cost Reduction Act (H.R. 6951), an omnibus higher education bill addressing myriad overhauls of the student loan process and college costs, a provision would require accreditors to focus on student outcomes, mainly completion and earnings, prohibit officials from serving on the boards of accreditors who accredit their institution, permit the switching of accreditors without U.S. Secretary of Education approval, and create new pathways for state-designated “quality assurance” bodies to act as accreditors.¹⁷ The measure, the first update of the Higher Education Act of 1965 since 2008, failed to make it off the House calendar. As part of its overhaul of the accreditation process, the bill would have amended the focus of accreditation to be on student outcomes, such as standards for:

- Consideration of the median total price charged to students for a program of study in relation to the median value-added earnings of students who completed such a program;

- Standards for consideration of learning outcomes measures (such as competency attainment and licensing examination passage rates);

- Standards for consideration of labor market outcomes measures (such as employer satisfaction surveys, employability measures, earnings gains, employment rates, or other similar approaches);

- Standards for consideration of student success outcomes measures (such as completion rates, retention rates, and loan repayment rates);

- A process to ensure that accreditors have a way to resolve student complaints; and

- A record of the institution’s compliance with value-added earnings and median total price.¹⁸

Building off the continuing discontent with the existing accreditation process, the White House also issued an Executive Order on “Reforming Accreditation to Strengthen Higher Education” on April 23, 2025. Among other items, the order directs the U.S. Secretary of Education to prioritize eliminating accreditor mandates supporting or promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion to instead focus on intellectual diversity; encourage competition among existing accreditors by facilitating the recognition of new entities; remove barriers to institutions transitioning to other accreditors; launch an experimental accreditation pilot site; and require accredited institutions to use race- or ethnicity-neutral program-level outcomes data to measure quality and improve accountability.¹⁹ The U.S. Department of Education lifted a prior hold on recognizing new accreditors in response. It also promoted a simplified approval pathway for institutions to switch to these new accreditors.²⁰

In the states, Florida took the first steps to address concerns with the existing system with the passage of Senate Bill 7044 (2022). The law requires the Sunshine State’s 40 public four-year institutions to seek new accreditors every 10 years.²¹ Critics argue that the provisions in the law, which require this change in accreditation regardless of whether individual institutions wish to change or not, will add bureaucratic barriers to institutions and risk reducing program quality and accountability. Meanwhile, proponents argue that the new perspective from changing accreditors will help shake up institutional stagnation and encourage innovation.²² According to the Florida Board of Governors, the cost for transitioning the state’s 12 public universities could amount to between $11 million and $13 million and cost approximately $250,000 per year per institution to maintain, in addition to being extremely resource- and staff-intensive.²³

Established in Article IX, Section 7 of the Florida Constitution, the Florida Board of Governors is the 17-member body that governs the State University of Florida and ensures a coordinated approach to the system’s operation as a whole and its individual member institutions. It comprises 14 members appointed by the Governor with state Senate approval. The state Commissioner of Education, the Chair of the Advisory Council of the Faculty Senate, and the President of the Florida Student Association are also members.

The following year, lawmakers in the Tarheel State copied the model, with the North Carolina General Assembly quietly passing House Bill 8 (2023) without debate. The measure, initially focused on computer science education requirements, included a provision that prohibited institutions from being consecutively accredited by the same agency, except in cases where an institution switched accreditors mid-cycle, and allowed institutions to seek a claim of action against individuals who submit false claims to an accrediting agency regarding an institution. Notably, however, the measure exempted professional, graduate, departmental, or certificate programs at institutions in fields such as law, pharmacy, engineering, and other similar programs as exempted by the Board of Governors of the University of North Carolina.²⁴ An original attempt to pass a similar measure in the Senate, via Senate Bill 680 (2023), failed to gain traction and, although signed by the governor, his office did raise concerns over the impacts of forcing changes of accreditors regardless of institutional desire. Unlike Florida’s legislation, no estimated impact was provided for the accreditation musical chairs in North Carolina.²⁵

Oklahoma legislators enacted Senate Bill 550 (2023) to remove the reference to a national or regional accrediting agency and permit any accrediting agency that meets U.S. Department of Education standards and does not violate Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education policy to be an allowable institutional accreditor.²⁶ Likewise, in West Virginia, lawmakers passed Senate Bill 488 (2023), which contained similar language requiring institutions to be allowed to choose any accreditor as long as they met state standards, while also mandating that state and federal accreditation rules be consistent.²⁷

More recently, in 2024, Tennessee lawmakers enacted Senate Bill 2528 (2024) to require institutions in the Volunteer State to regularly update accreditation policies to align with changes from the U.S. Department of Education or Congress. Additionally, the law prohibits accrediting agencies from compelling or otherwise imposing upon institutions to violate state law or policies as a part of the accreditation process.²⁸ In 2025, the Texas Legislature enacted Senate Bill 530 (2025), which adds language allowing any recognized accreditation agency recognized by the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board to accredit institutions, replacing existing language mentioning SACSCOC.²⁹

A Growing Trend in the South

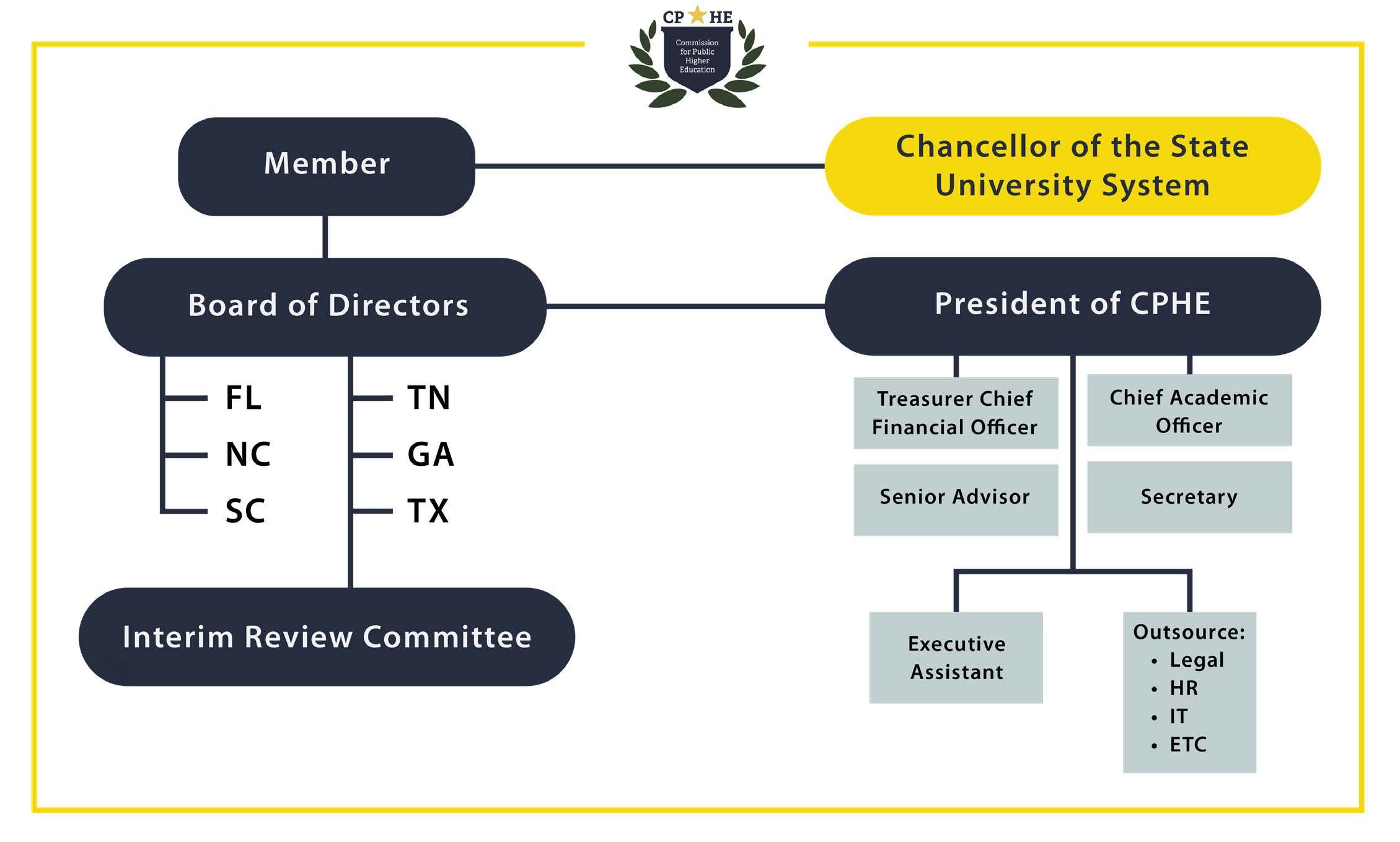

Concurrent with the actions mentioned above, a group of Southern states has proposed the formation of the Commission for Public Higher Education (CPHE) to serve as a new accreditor governed by state-regulated systems instead of private entities. The CPHE, led by Florida and joined by Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas, would emphasize academic rigor, student outcomes, and efficiency to position itself as a less bureaucratic and more output-focused alternative to existing accreditor organizations. The transition would be up to individual institutions and systems in the participating states, leading to a gradual or phased-in approach.³⁰

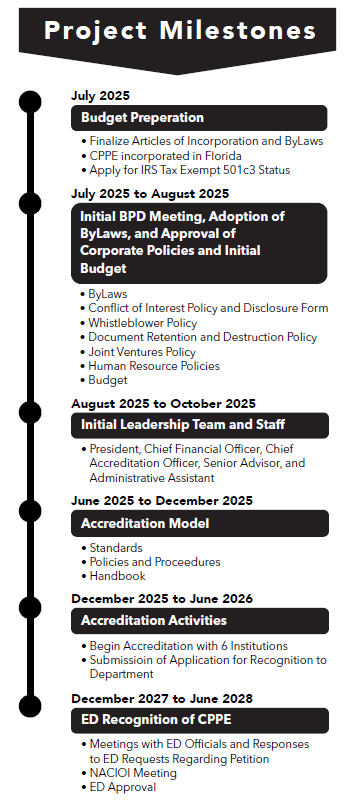

FIGURE 3. Proposed CPHE Project Timeline

However, despite the growing roster of states and institutions committed to the CPHE, details are scarce regarding the exact standards the commission will utilize or any differences in process and policy from existing accreditors. While proponents have highlighted the benefits of better aligning accreditation with outcomes and state-led higher education agencies, opponents worry this move will lead to increased government interference in higher education, curriculum, staffing decisions, and other areas of educational independence. The commission’s birth became official with the Board of Governors of the University System of Florida’s approval of the CPHE business plan during its July 11, 2025, business meeting.³¹

FIGURE 4. Proposed General Organizational Overview of CPHE

While the initial six seats on the Board of Directors will comprise those appointed by the six participating state institutional systems, the bylaws allow for additional directors to be appointed in the future from subsequent states that join the commission or even non-state system members who may possess “content and policy expertise.” The commission’s start-up costs of $4 million are covered via an appropriation from the Florida Legislature, with additional funds or labor costs to be supported by allocations comparable in expense to the five other participatory systems. Identical to existing accreditors, the commission anticipates its long-term funding stream based on accreditation fees, consulting or advising rates, technical assistance services, or training programs beginning in late 2027 or early 2028.³³

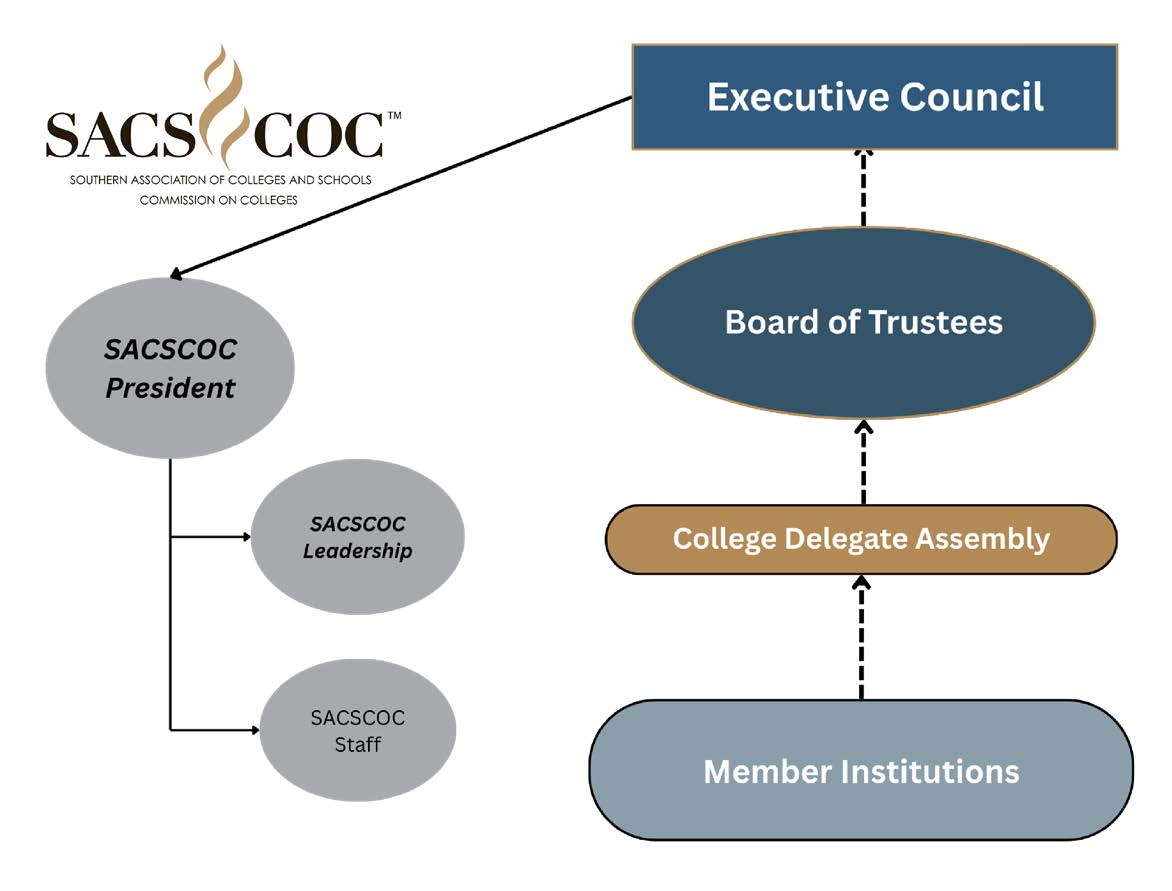

FIGURE 5. SACSCOC General Organizational Overview

Comparatively, both current regional accrediting commissions are far larger due to the sheer number of institutional members. For example, SACSCOC operates via a 77-member Board of Trustees elected from the College Delegate Assembly, which comprises one voting member, the institution’s chief executive officer, from each member institution.³⁵ Further, a 13-member Executive Council, elected by the Board of Trustees, comprises a representative from each of the 11 Southern member states, plus a public at-large member and the Board of Trustees’ chair. The council serves as the executive arm of the Board of Trustees. It is responsible for interpreting commission policy and procedure and functioning on behalf of the board during interims between sessions.³⁶

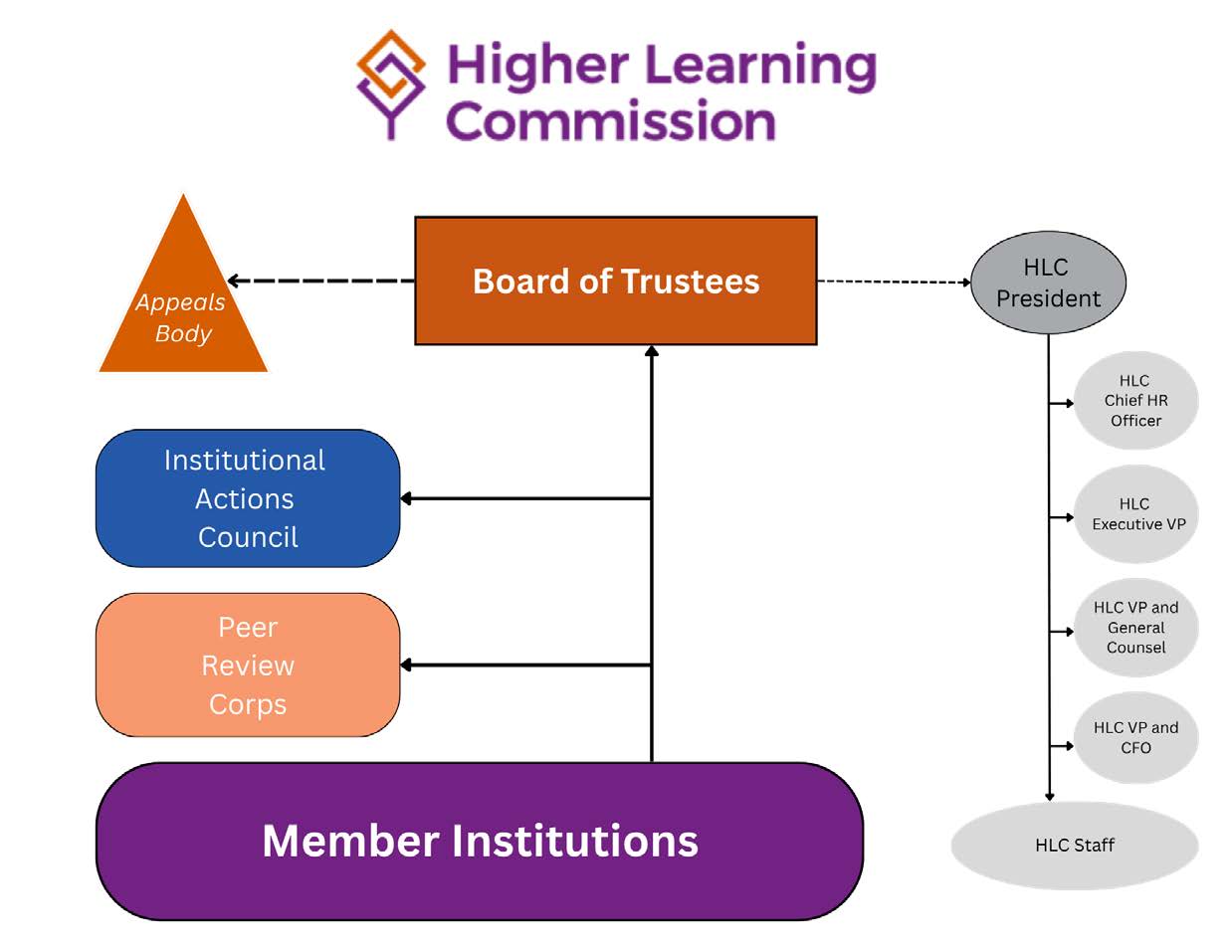

Likewise, the HLC operates with large boards and subgroups due to its large membership base. It maintains a Peer Corps of more than 1,500 faculty and administrators from member institutions who evaluate whether applicants or members meet the respective criteria for accreditation or reaccreditation. The Institutional Actions Council advises the Board of Trustees and makes recommendations based on peer reviews. It has nearly 125 members representing member institutions and the general public.³⁸ The Board of Trustees makes final decisions regarding actions on prospective or member institutions and is also responsible for setting the commission’s accreditation policies and ensuring all fiduciary responsibilities are met. The Board of Trustees has no more than 21 and no fewer than 16 members elected by the HLC’s member institutions to initial four-year terms with an option for subsequent two-year renewals, which cannot exceed a total term length of 12 years.³⁹

FIGURE 6. HLC General Organizational Overview

Conclusion

With continuing federal and state support for rethinking the accreditation process, expect more states in the South and beyond to follow the CPHE states’ lead or form their own competing state-led accreditors, as well as remove any vagueness in state law that allows accreditors control of institutional policy or compliance with state laws. While there have been some concerns surrounding the creation of this new accreditor, the Florida Board of Governors student and faculty board members joined the other 15 members in unanimously approving the creation of the CPHE.⁴⁰ With its leaner organizational structure, Southern policymakers hope that the CPHE will provide a much-needed impetus for rethinking the byzantine and bureaucratically mired accreditation process, something there has historically been support for reforming from across the political and geographic spectrum.⁴¹

End Notes

- “Accreditation in the U.S.,” U.S. Department of Education, accessed August 2025.

- Dr. Christy England, “Accreditation Overview,” Presentation to the Board of Governors of the State University System of Florida, August 26, 2022.

- “Accreditation in the U.S.,” USDOE.

- “Definition of Peer Review,” Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, updated September 2020.

- “Authority,” National Advisory Committee on Institutional Quality and Integrity, U.S. Department of Education.

- Public Law 102-325, 102nd Congress (1992).

- Public Law 110-315, 110th Congress (2008).

- “Accreditation in the U.S.,” USDOE.

- Ibid.

- “Blueprint for Reform: Accreditation,” The James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal, October 27, 2024.

- Garrett Shanley, “Florida spends $4 million on new ‘ideology-free’ college accreditor,” Miami Herald, July 12, 2025.

- Jason Armesto, “Georgia joins five Southern states to form new accreditation agency,” The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 6, 2025.

- “CHEA Almanac,” Council for Higher Education Accreditation (2022-2023).

- “College Accreditation Explained,” Education Next, June 13, 2018.

- “Accredited and Candidate List,” Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges, February 2025.

- “Directory of Institutions,” Higher Learning Commission (2025).

- H.R. 6951 – College Cost Reduction Act, 118th Congress (2024).

- Ibid.

- “Reforming Accreditation to Strengthen Higher Education,” Executive Orders, The Office of the President of the U.S., April 23, 2025.

- “U.S. Department of Education Expands Accreditation Options for Colleges and Universities,” Press Release, U.S. Department of Education, May 1, 2025.

- Florida Senate Bill 7044 (2022).

- Josh Moody, “Florida’s Accreditation Shuffle Begins,” Inside Higher Ed, August 30, 2023.

- Ibid.

- North Carolina House Bill 8 (2023).

- Josh Moody, “North Carolina Forces Changes to Accreditation,” Insider Higher Ed, October 10, 2023.

- Oklahoma Senate Bill 550 (2023).

- West Virginia Senate Bill 488 (2023).

- Tennessee Senate Bill 2528 (2024).

- Texas Senate Bill 530 (2025).

- Armesto, “Georgia joins five Southern states to form new accreditation agency.”

- “Board of Governors Approves Creation of the Commission for Public Higher Education,” Press Release from the State University System of Florida, July 11, 2025.

- “Updated Business Plan,” State University System of Florida, July 11, 2025.

- Ibid.

- “Commission Organization and Elected Members,” SACSCOC.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Decision-Making Processes,” HLC.

- “Leadership,” HLC.

- “Decision-Making Processes,” HLC.

- Ani Goñi-Lessan, “Board of Governors approves new accreditor for Florida universities in win for DeSantis,” Tallahassee Democrat, July 11, 2025.

- “Florida spends $4 million on new ‘ideology-free’ college accreditor,” Miami Herald.