Which Southern States Require Country-of-Origin Labels for Restaurant Seafood?

DOWNLOADThe Acadiana region of Louisiana is known for many things—George Rodrigue’s Blue Dog, the up-tempo rhythms of zydeco music, and former LSU Coach O’s gravelly accent—but nothing compares to its food. The region is lauded for its many dishes, including seafood staples like shrimp creole, crawfish étouffée, Cajun fried oysters, blackened catfish, and the ever-crowd-pleasing crawfish boil. These culinary delights trace their roots to Creole and Cajun traditions that used what was available from the nearby waters.

It was headline news then when 33 percent of surveyed restaurants in Lafayette, the largest city in the Acadiana region, were caught serving imported shrimp. Some of the restaurants even advertised the imported shrimp as local, genuine Gulf shrimp, which may put them at risk of violating Louisiana state law. Under the law, any shrimp or crawfish produced or farmed outside of the United States and sold in a Louisiana restaurant must label their menus with the phrase “some items served at this establishment may contain imported crawfish or shrimp.”

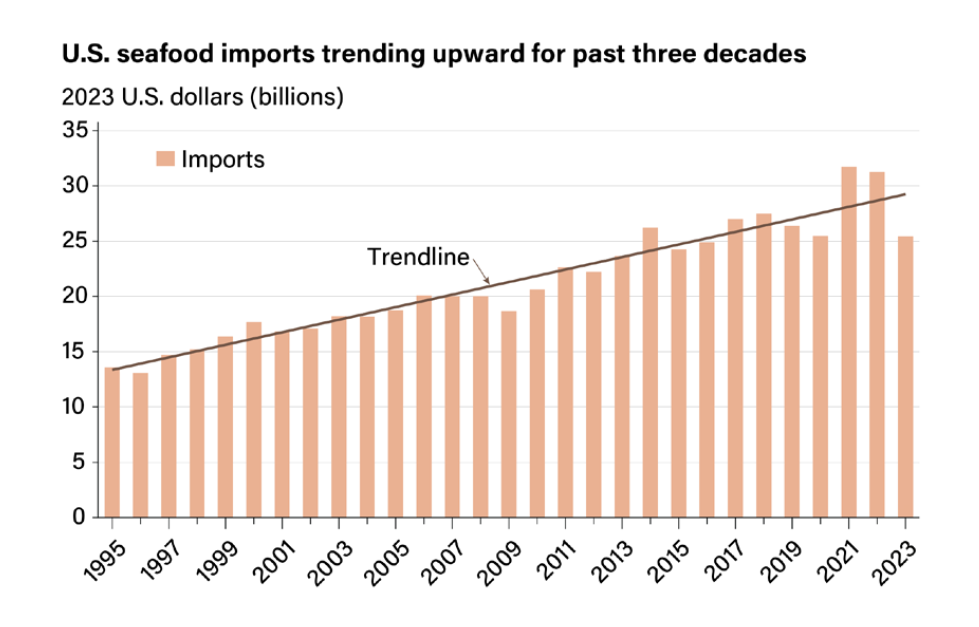

The law, which passed with no opposition and went into effect in 2019, aimed to address two issues. The first is the continued influx of imported seafood from countries like Chile, India, and Vietnam. The domestic shrimp industry, for example, has been hit particularly hard by imported products, according to the Louisiana Shrimp Association. The organization says that imports have “caused a significant loss of revenue for small family-owned fishing businesses and has caused unfair competition for domestic shrimp producers throughout the United States.” The seafood industry accounts for one out of every 70 jobs in Louisiana and had a $838 million impact on the Pelican State in 2022 (the last available year for comparative data).

The second issue is health concerns. A 2020 study conducted by researchers at Louisiana State University (LSU) found that more than two-thirds of samples of imported shrimp purchased from establishments throughout the Baton Rouge area contained residues of veterinary drugs, which contained chemicals like nitrofurantoin, malachite green, oxytetracycline, and fluoroquinolone that can be harmful to humans.

Louisiana is not the only state looking to support its seafood industry. Among the nine coastal Southern states, seafood is big business with an overall economic impact of $14.5 billion. Beyond this, a 2022 study from researchers at the University of Florida found that restaurant consumers across the U.S. strongly prefer entrées with transparent information like country-of-origin labels, as well as specific species information and sustainability ratings.

2022 Economic Impact of the Seafood Industry in Coastal Southern States

| State | Economic Impact (In Millions) (2022) |

|---|---|

| Alabama | $196 |

| Florida | $8,207 |

| Georgia | $1,275 |

| Louisiana | $838 |

| Mississippi | $165 |

| North Carolina | $377 |

| South Carolina | $78 |

| Texas | $2,049 |

| Virginia | $1,339 |

It is no surprise, then, that other states in the region followed Louisiana’s lead and passed legislation requiring labels to inform diners of the source of their seafood. In Alabama, for example, restaurants must label fish or shrimp sold with the country of origin. If the seafood is caught or raised in the United States, the label may include the state, but it is not required. The label must be visible during the final point of sale; in the case of menus, it must appear using the same font and size as the offered item. The law went into effect in October 2024 after receiving full support from all voting members.

Mississippi recently passed a similar law without any opposition, which went into effect in July 2025. It states that the country of origin must be listed for seafood items on the menu and printed in the same font style and size as the item. If the restaurant only sells shrimp from the United States, then the food service establishment may generally disclose this in a prominent location in lieu of disclosure on the menu.

In Texas, legislation that focused solely on shrimp was recently passed (with only three votes against it) and goes into effect in September 2025. The bill states that “a restaurant shall not label or represent imported shrimp as ‘Texas shrimp,’ ‘American shrimp,’ ‘domestic shrimp,’ or ‘Gulf shrimp.’” This bill was an effort to support the state’s shrimping industry and came after a January 2025 study by SeaD Consulting found that more than half of the 44 surveyed restaurants in the Houston area were serving imported shrimp despite advertising it as local.

Similar bills have been introduced in the House chambers in Florida and South Carolina, but have not been voted out of committee. In 2025, HB 117, requiring Georgia restaurants that serve imported shrimp to label menus with either “Foreign Imported” or “Foreign Imported Shrimp,” passed the Georgia House with 165 of 172 voting members in favor, but has not yet moved forward in the Senate.

With the above exceptions, country-of-origin labeling (also known as “COOL”) does not generally apply to restaurants. Under federal law, restaurants are exempt from country-of-origin seafood labels, though larger-scale commercial sales are required to do so. Therefore, in coastal Southern states that haven’t passed labeling laws, a seafood restaurant—even one along the water—could be selling imported seafood and not locally caught fish. For example, a May 2025 SeaD Consulting study of shrimp sold at 44 different restaurants in Charleston, South Carolina, found that 90 percent of the establishments were selling imported shrimp and not local, Lowcountry shrimp, as they had led customers to believe.

However, states without country-of-origin label laws may still have regulations against mislabeling seafood. Florida’s Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, for example, makes it clear that mislabeling seafood’s country of origin is illegal. In these cases, it may be legal for a restaurant to forego mentioning where its seafood comes from, so long as they don’t advertise imported seafood as local.

In states that have either enacted seafood labeling laws or seek to have regulations against mislabeling seafood, the penalties for violations vary. In Texas, the decision is left up to the state’s Department of State Health Services. In Alabama, the maximum penalty for a restaurant is $1,000, and that only occurs after four prior offenses (with fines ranging from $100 to $500). Mississippi allows for a maximum penalty of $10,000. Louisiana’s fines initially ranged from $1,000 to $2,000 after two previous offenses, but legislation in 2024 raised the fines to $50,000 after two previous offenses.

As more coastal Southern states look to support their seafood industries in the wake of increasing imports, more laws may be passed requiring labels on imported seafood served in restaurants. In addition, seafood labeling laws may prevent the spread of unwanted contaminants found in some imported products. Beyond this, these laws may bolster diners’—both locals and tourists alike—confidence that the dishes they select come from nearby waters or from far-off seas.